Biometric efficiencies

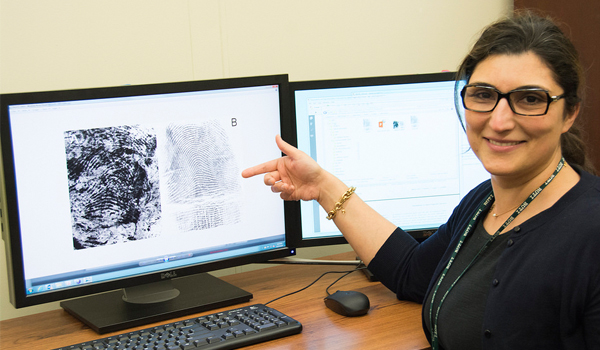

Researchers have taught machines to assess latent fingerprints, which could lead to automation of a critical process and save considerable forensic time and resources.

When the badly-beaten bodies of South London shopkeepers Thomas and Ann Farrow, were discovered in their home in early 1905, the police officers in charge of the case saw the perfect opportunity to make use of the latest weapon in their crime-fighting arsenal fingerprints. It was just three years since the first English court had admitted fingerprint evidence in a petty theft case, but this would be the first time it had been used in a murder. The cashbox in the Farrow home had been emptied and one print on it did not match the victims or any of the handful of index cards at Scotland Yard. Eyewitnesses soon identified brothers Alfred and Albert Stratton as the most likely suspects and, once they were arrested, Alfred Strattons right thumb was matched to the print on the cashbox. Within weeks, the brothers had been convicted and hanged. Since then, fingerprints have been considered, both in the courts and in the eyes of the public, to be an infallible method of identification. Despite the development of DNA profiling for criminal investigation, fingerprints remain the most common forensic evidence recovered from a crime scene. They carry so much weight as evidence that lawyers often advise their clients to plead guilty if they cannot explain how their prints came to be found at a crime scene. However, in recent years, research has shown that fingerprint examination can produce erroneous results. A 2009 report from the National Academy of Sciences found that results are not necessarily repeatable from examiner to examiner, and that even experienced examiners might disagree with their own past conclusions when they re-examine the same prints at a later date. These situations can lead to innocent people being wrongly accused and criminals remaining free to commit more crimes. A 2011 public inquiry into the case of a former police officer wrongly accused of leaving her print at a crime scene concluded that she was the innocent victim of human error. Other recommendations suggested that print evidence cannot be treated with 100 per cent certainty or on any other basis suggesting that fingerprint evidence is infallible. It recommended that any features in a print should be demonstrable to a lay person with normal eyesight and that explanations for any differences between a mark and a print require to be cogent if a finding of identification is to be made. The inquiry also issued a series of recommendations, including fingerprint experts acknowledging their findings were a matter of opinion rather than fact. But scientists have been working to reduce the opportunities for human error. Earlier this month, scientists from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and Michigan State University reported that they had developed an algorithm that automates a vital step in the fingerprint analysis process. We know that when humans analyse a crime scene fingerprint, the process is inherently subjective, said Elham Tabassi, a computer engineer at NIST and a co-author of the study. By reducing the human subjectivity, we can make fingerprint analysis more reliable and more efficient. If all fingerprints were high-quality, matching them would be simple. For instance, computers can easily match two sets of prints that are collected under controlled conditions, such as those taken at a police station or, more commonly, when someone uses a fingerprint scanner on a smartphone. But at a crime scene, theres no one directing the perpetrator on how to leave good prints, said Anil Jain, a computer scientist at Michigan State University and another co-author of the study. As a result, fingerprints left at a crime scene so-called latent prints are often partial, distorted and smudged. Also, if the print is left on something with a confusing background pattern, such as a £20 note, it may be difficult to separate the print from the background. That is why when an examiner receives latent prints from a crime scene, their first step is to judge how much useful information