The Covid effect

Danny Shaw, head of Strategy and Insight at the crime and justice consultancy Crest Advisory, examines the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the latest crime statistics.

The publication of the official crime figures is often a day of confusion with data from the police, which measures offences recorded by forces, telling one story and the Crime Survey of England and Wales, based on people’s experiences of crime, telling another.

The latest figures, from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), present a different problem because they include a long period, of more than six months, when we were living either under lockdown or bound by other restrictions to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Limits on travel and social contact, together with the closure of pubs, clubs and restaurants, reduced opportunities for theft and violence in public places, causing sharp falls in many types of offending, meaning it’s almost impossible to make meaningful comparisons with previous years and assess overall trends.

But the statistics do give us a valuable insight into the crimes which appear to have flourished during the pandemic… and, from separate Home Office data, we can see whether the reduced caseload has allowed the police to detect more crimes, which would be reflected in an uptick in charging rates.

First, a summary of the figures. They show that in the 12 months to the end of last September, offences recorded by police dropped by six per cent to 5.7 million offences compared with the same period the year before:

- Burglary down 20 per cent;

- Robbery down 17 per cent;

- Firearms offences down seven per cent;

- Sexual offences down six per cent; and

- Knife crime down three per cent.

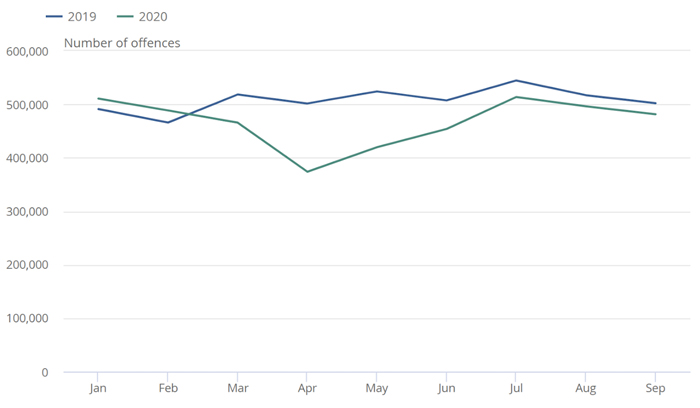

The reductions were steepest between April and June, but crime was edging back to pre-pandemic levels during July, August and September, as restrictions were relaxed.

The Crime Survey, which includes offences that are not necessarily reported to police, also estimates that the number of victims between July and September returned to a similar level as in the pre-coronavirus period, after a 19 per cent decrease in April to June, compared with the previous quarter.

We know, however, from provisional data from the National Police Chiefs’ Council that crime rates fell again in the last few months of 2020 as the tiered system came into effect, a ‘firebreak’ was introduced in Wales and England entered a second lockdown. The most recent figures were published last week.

So, what crimes have gone up, despite all the restrictions?

Drug offences recorded by police rose by 16 per cent compared with the previous 12 months. Between April and June, as demand for officers in the night-time economy plummeted, resources were diverted to proactive policing in crime hotspots where dealers stood out more in quieter streets. Operation Venetic, a National Crime Agency investigation in which many hundreds of suspected traffickers and dealers were arrested in the UK after the takedown of an encrypted global communication system, undoubtedly played a part too.

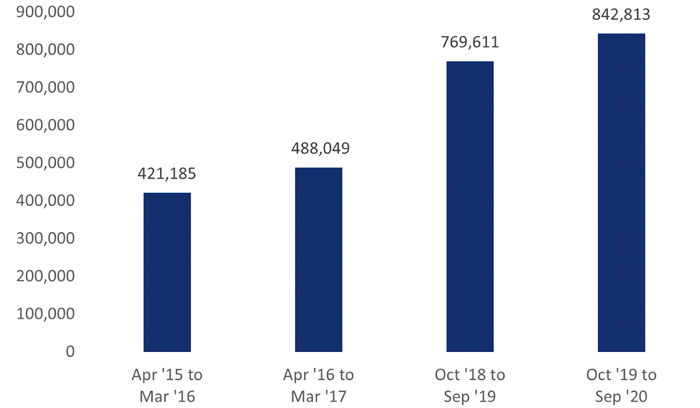

As charities and support groups feared, there also appears to have been a rise in recorded domestic violence. Offences flagged by police as related to domestic abuse went up ten per cent to a record 842,813 in the year ending September 2020. During the 12-month period they accounted for 17 per cent of all crimes, excluding fraud, and 37 per cent of all violence against the person offences. Some of the rise may reflect greater awareness of the problem and an increased willingness to report it, particularly during lockdown when some victims felt more at risk.

The other main crime type that seems to have bucked the trend since the pandemic reached our shores is fraud, with a surge in various online scams as our lives moved increasingly indoors and onto screens.

Overall levels, based on police data and Crime Survey estimates, are stable. But Action Fraud, the national reporting centre, said there had been a 27 per cent rise in fraud relating to online shopping and auctions and UK Finance, which represents more than 250 firms in banking and finance, said ‘remote banking’ fraud went up a staggering 61 per cent, reflecting how many of us now use internet, telephone and mobile banking. There was also a 53 per cent rise in reports of emails and social media accounts being hacked.

Investigating fraud is often regarded as the “unsexy” side of policing, but it is the most common type of crime, with an estimated 4.4 million offences in the 12 months to the end of September. With elections for police and crime commissioners just a few months away, candidates would do well to consider strategies to tackle the problem.

Separately to the ONS data, the Home Office has released its latest set of ‘Crime Outcomes’, which show what happened to offences recorded by police in the 12 months to last September. The data, for forces in England and Wales, exclude Greater Manchester Police, which has been reprimanded by the Inspectorate of Constabulary for failing properly to record some offences.

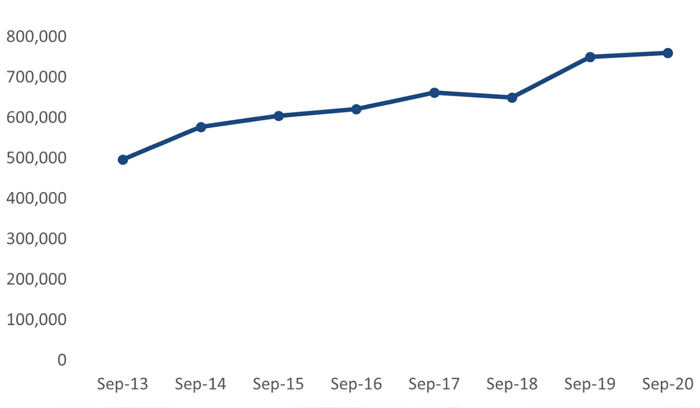

The way outcomes were compiled changed in 2014/15. That year, 15.5 per cent of crimes resulted in a suspect being charged (or issued with a summons to appear in court). Since then, charging rates have declined almost continuously. By March 2020, they were at seven per cent. It is worth spelling out what that meant – for every 100 offences recorded by police, just seven led to a prosecution.

The two sets of outcome figures since March 2020 suggest there has been some small improvement. You would have expected that given that the police investigative caseload has been reduced at a time when officer numbers have been rising. What is concerning is that the increase in the proportion of charged cases appears to have fallen back when restrictions were eased last summer, from 7.4 per cent in the year to the end of June, to 7.3 per cent in the 12 months to September.

There are signs police are handing out more informal warnings – as opposed to steering cases towards the courts. Warnings about the use of cannabis and khat and community resolutions, where police deal with low-level incidents by getting people to apologise or pay for or repair damage, were applied in 2.7 per cent of cases compared with 2.3 per cent the year before.

But formal out-of-court disposals, such as cautions, remain a rarity, just 1.4 per cent overall. It begs a question Crest has asked in its reports into the impact of Covid on the criminal justice system: as pressures on the courts intensify in the months and years ahead, should police make better use of schemes to divert some offenders away from prosecution?

This article originally appeared on the Crest Advisory website and is republished here by kind permission. You can read the original here.