Highly-charged debate

Taser has helped resolve dangerous situations without deadly force on countless occasions, but when it fails to work as intended, the results can be serious, for officers and offenders alike. With the new X2 model producing a lower charge than its predecessor, Police Professional reports on concerns about its effectiveness.

The body-worn video (BWV) footage from Gwent Police depicts the type of daily scenario faced by an increasing number of officers. Responding to a report of a disturbance at a property in Caerleon, Wales, two officers arrive at the top the stairs to find a man standing behind a set of glass doors, a large kitchen knife in each hand.

The man refuses to put the weapons down and becomes more agitated, indicating he will stab the first person to come through the door. The officers decide to deploy their Taser and, working in tandem, wait for the right moment so that one can open the door and the other take a shot.

This is precisely the situation Taser was created for – when officers need to protect themselves under threat of potentially lethal violence. The electrical charge generated by the device ‘locks up’ a person’s muscles for a few seconds, rendering them unable to move. This gives officers an opportunity to disarm and handcuff a suspect, all without inflicting serious injury.

When the right moment presents itself, the door is pushed open and the Taser is discharged as the man charges towards one of the officers. The BWV footage shows the barbs hit him in the abdomen and the distinctive crackle of the Taser, indicating that electricity is flowing into the target, can be heard. But the man keeps coming forward, thrusting the knives and forcing the officer by the door to jerk back to avoid being stabbed in the stomach.

A second Taser cartridge is discharged just as the first officer manages to grab the man’s hands, forcing him against the wall. The man then falls to the ground, still thrusting the knives forward, before he is eventually disarmed and taken into custody.

Thankfully the confrontation ended without serious injury and the man was later sentenced to four years in prison, but it illustrates a troubling weakness – Taser does not always work as intended. And when it fails to disable a suspect, the results can be life threatening – both for the officers involved and those they are attempting to detain.

In the US there were more than 250 fatal police shootings between 2015 and 2017 following the failure of Taser to incapacitate a suspect. In 106 of these incidents, the suspect reportedly became more violent after receiving the electric shock.

Similar incidents have occurred in the UK. In March, a coroner’s court in Bedfordshire heard the case of Josh Pitt, a 24-year-old who took his fiancée hostage in 2016. Armed officers attended the scene and found Mr Pitt had barricaded himself into a room and was armed with kitchen knives.

Coroner Ian Pears said: “A Taser was fired, but the Taser was ineffective.”

Although the coroner noted there were disputes and differences between the facts of what followed, the confrontation ended when Mr Pitt was shot at close range and subsequently died. The coroner ruled he had been lawfully killed.

In October 2015, officers from the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) were called to a disturbance at Claremont Road in northwest London where they encountered Joseph Hive who was wielding two knives. When he refused to drop the weapons, a Taser was deployed. It had no effect. Mr Hive was tasered three more times but continued to lash out with the knife.

An officer then drove a police vehicle towards Mr Hive at 9mph, intending to knock him over, but he began slashing at the tyres of the car. Officers then tasered Mr Hive five more times, still without any effect.

Finally, the decision was taken to deploy a firearm. After a single shot, Mr Hive fell to the ground and was taken into custody with chest and arm injuries.

The case was investigated by the then Independent Police Complaints Commission – now the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) – which found officers had used “necessary and proportionate” force. A spokesperson said: “Taser was fired a total of 11 times. The man was found to be wearing extra clothing, which we believe reduced the effectiveness of Taser on at least one occasion. Yet he still posed a real danger to officers, leaving them with no option but to use further force.”

In January, MPS officers responded to a call from a leisure centre in Greenwich where a man who had not paid to enter was refusing to leave. Officers confronted the man who immediately became aggressive. When told the officers were armed with a Taser, the man goaded them to shoot him.

In a video of the incident, recorded by a member of the public and widely shared on social media, the man paces around the officers, becoming increasingly aggressive, and then approaches the officer with the Taser. The weapon is discharged but the man then pulls the barbs from his chest, throwing them back towards the officer before storming off.

More BWV footage recorded by Sussex Police in 2016 shows four officers confronting an armed man hiding in the doorway of a brick shelter at the base of a block of flats. One of the officers discharges his Taser but the man surges forward, swinging a claw hammer at the officers and pulling at least one of the barbs from his body, breaking the electrical circuit. A second officer discharges his Taser but again there seems to be no effect.

Taser does not always work as intended. And when it fails to disable a suspect, the results can be life threatening.

As one of the officers attempts to parry the blows from the hammer with her baton, Taser is discharged for a third time, again with little effect, and it is only when one of the officers manages to get in close and strike at the man’s legs repeatedly that he is finally subdued.

Tasers are manufactured by US company Axon, which has a virtual global monopoly on the device. Axon’s slogan is ‘Protect Life’ and its Tasers are designed to subdue by causing neuro-muscular incapacitation (NMI) in their bodies, rendering them unable to move. In a statement to Police Professional, Axon said that during pre-release testing “ NMI was achieved at or near 100 per cent of the time” under ideal conditions.

With such ideal conditions rarely encountered on the street, studies have shown that the devices – particularly newer models – are significantly less effective than this. In March 2016, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) – an early adopter of Taser – released a report showing that the devices had subdued suspects in only 53 per cent of uses during 2015. This was 11 per cent less than the figure for the previous year when officers had primarily been using the older X26 model instead of the newer X2.

An investigation suggested that ineffective Tasers were a recurring element in a number of the city’s police shootings. There were 21 fatal police shootings by the LAPD in 2015 and in at least five of those incidents LAPD officers had used Taser before resorting to a firearm.

Across the US, a recent investigation conducted by American Public Media Reports identified 258 fatal police shootings between 2015 and 2017 in which a Taser had been ineffective. In around 100 of those cases the subject reportedly became enraged or more aggressive after a Taser had been discharged.

Axon disputes these figures and says data from police departments does not accurately reflect Taser effectiveness because it may not include instances when a suspect was subdued after an officer merely ‘displayed’ or threatened to discharge a Taser. The company argues that the sight of the weapon can be a significant deterrent to a suspect and those incidents should count as effective use.

Such is the case in the UK where 83 per cent of incidents involving a Taser do not involve the device being discharged. There are, however, concerns that in incidents where officers have to discharge their Taser to protect themselves, the device may prove ineffective more often than expected.

In a statement, Axon said: “Although law enforcement users are trained on these required conditions, they are often confronted with circumstances that may prevent these conditions from being met.”

Concerns are mostly around the X2 model – currently being rolled out to police forces across the UK – which produces only half the electrical charge of its predecessor.

Power cut

Rick Smith, the 48-year-old founder and chief executive officer of Axon, has built his company into one of the top suppliers of technology to police forces around the world and jokingly refers to himself as the “Steve Jobs of law enforcement”. Axon produces BWV cameras, surveillance drones and virtual-reality simulators, but is best known for the Taser.

The device was invented in the early 1970s by Jack Cover, a physicist living in Southern California. Mr Cover named his creation ‘Taser’ as an acronym taken from a young adult science fiction novel he read as a child – Tom Swift and his Electric Rifle. He set up a company called Tasertron to build and sell the device, but instead sold the patents and moved on.

Mr Smith co-founded his first company with his brother Tom in September 1993, soon after leaving university. With a keen interest in electric weapons he contacted Mr Cover, who at the time was developing a new type of Taser that used compressed gas rather than gunpowder to propel its barbs.

Together they built a product called the Air Taser, but the fledgling business, operating under the name Taser International, almost went bankrupt because the patents held by Tasertron prevented them from selling to police departments. The patent finally expired in 1998 but police were still not interested in the Air Taser as it simply was not effective.

The Air Taser emitted a charge of 70 microcoulombs per pulse, but the company found this was not enough to stop determined suspects from overcoming its incapacitating effects. In a demonstration in Prague, Mr Smith reported that a “pumped up” volunteer “managed to fight his way through” the charge of the Air Taser.

The company worked on boosting the power of its devices. Mr Smith told the patent office it was a matter of public safety; if police officers relied on too-weak a weapon to stop suspects, there could be “dire consequences”.

In 1999, the company unveiled the M26, the first electroshock weapon specifically designed to lock up muscles as well as induce pain. Each pulse delivered 85 microcoulombs of electricity, according to early specifications published by Taser.

In 2003, the company boosted the charge again and released the X26, which delivered 100 microcoulombs per pulse. It became its most successful product, almost doubling revenues and allowing the Smith brothers to buy out Tasertron and achieve market dominance.

Last year, the company, by then known as Axon, reported sales of $420 million – up 22 per cent on the year before – with $253 million coming from the supply of Tasers.

In 2008, more than four years after the launch of the X26, the company learnt that the output of the weapon could be as much as a third higher than it had disclosed in its early product information. A company-funded study showed that when the darts impale flesh rather than clothing, the X26 can actually deliver a charge of up to 135 microcoulombs.

There have been at least 17 deaths linked to the use of Tasers since they were introduced in the UK in 2003 and coroners have attributed more than 150 such deaths around the world to the Taser. Axon insists that its weapons are never to blame and that such deaths result from drug use, underlying physiological conditions such as heart problems, or other use of force issues.

According to Axon, only 24 people have ever died through Taser use – 18 from fatal head or neck injuries in falls caused by a Taser strike, and six from fires sparked by the weapon’s electrical arc – but not a single person has died from the direct effects of the Taser’s powerful shock.

Tasers are the most safe and effective less-lethal use of force tool available to police.

Despite this, in 2009 Axon issued its first cardiac warning, suggesting that officers avoid shooting offenders in the chest area (briefly advising shooting suspects in the back as there is more muscle for the electricity to flow through).

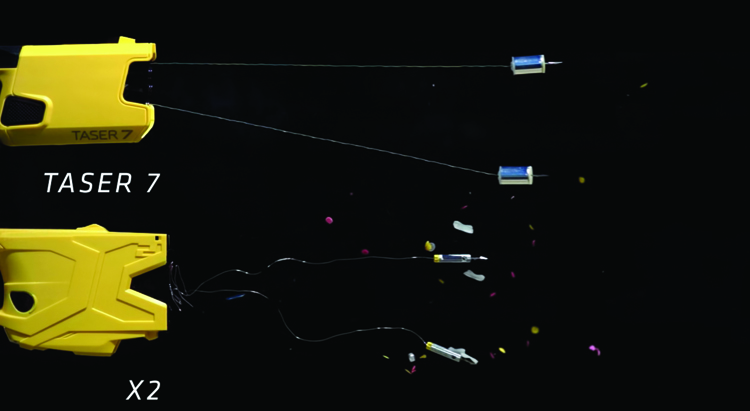

It then reduced the power of its next generation of Taser. The newest models, the X2 and the X26P, had roughly half the electrical charge of the X26. The typical output of both is 63 microcoulombs.

At the time this decision was taken, Axon was receiving a growing number of lawsuits filed by the families of those who had died after Taser was used on them. By 2011, there were 55 claims in place. Since introducing the new models, the number of lawsuits has fallen significantly, with only eight currently active against the company.

Training materials for the X2 Taser state “63 charge units is about the optimal level to achieve incapacitation while maximising safety” and that it has a “significantly improved safety margin”.

Axon says its own tests show “no discernible difference” in the takedown abilities of the X2 and the X26.

The company told Police Professional: “It should be noted that ‘power’ does not equal charge. Rather, charge is only one of three parameters that contribute to the ability to cause NMI. The other two parameters – pulse duration and pulse frequency – are just as important and all three parameters must be considered together. Generally speaking, increasing the pulse frequency and charge, and decreasing pulse duration, increases the ability to cause NMI.”

Andy Gray, a former MPS and Lincolnshire Police officer who now works for Axon told Police Professional: “Having been ‘tased’ by both, I can tell you that they are both very effective.”

Even so, the Taser X2 training PowerPoint that Axon supplied to US police departments states that people can sometimes fight through the shock of a Taser or pull the darts out of themselves, especially when the X2 is used at close range.

This reduction in power did not go unnoticed by the UK Government when it assessed whether the new device should be introduced in 2016. The Scientific Advisory Committee on the Medical Implications of Less-Lethal Weapons noted: “The electrical charge carried by the pulse waveform of the Taser X2 is rated at about half that of the waveform of the X26. Although presently speculation, one possible implication of the lower charge is that the degree of neuromuscular incapacitation – and possibly pain – induced by single cartridge discharge from the X2 may be less than that from the X26.

“If this results in decreased effectiveness, this may lead officers to use alternative, potentially more injurious, forms of force or increase the frequency of deployment of the second cartridge bay. The latter may lead to an increase in the frequency of probe-associated injuries to the skin and underlying organs and tissues, as well as enhancing the risk of fall-associated injuries.”

In March 2017, the then Home Secretary Amber Rudd said she was authorising the introduction of the Taser X2 for UK forces. With the X26 no longer supported and no other manufacturers in the sector, forces had no choice but to move to the X2 as a replacement for outdated models.

However, in a lawsuit filed in Houston, Texas, in 2017, police officer Karen Taylor alleged the X2 was too underpowered to be effective in the field, so much so that it failed to stop a mentally-ill woman from attacking her. The incident left Officer Taylor with injuries that ended her eight-year police career, she said.

In October 2015 she had responded to a call for assistance from a store in North Houston where a homeless woman was taking drinks off the shelves and consuming them without paying for them. When Officer Taylor arrived, the woman flew into a rage and attacked her. She discharged her X2 and the “woman went down”, but immediately got back up. The officer discharged her second cartridge but again this proved ineffective.

Officer Taylor contends Axon “hid” the power reduction to persuade police to swap their old X26 models for the new X2. The reduction in power exposes officers to violence and raises the odds they will draw a service pistol as backup, her lawsuit alleges.

“A police officer has to have a reliable piece of weaponry to feel safe,” Officer Taylor said in an interview. “Otherwise, it’d be like sending an officer into a gunfight with a water gun.”

In March this year, the US District Court in Houston denied Axon’s motion for summary judgment in the case. The judge found that the evidence, and reasonable inferences from it, raised legitimate questions as to whether the X2 was underpowered as designed and whether Officer Taylor’s career-ending injuries were caused by the failure of that weapon to incapacitate her assailant.

Judge Johnson wrote: “The jury is capable of logical, common sense conclusions about what could happen if police officers were armed with less effective [Tasers] and lost confidence in their use.”

The case will go to trial in November.

Another lawsuit has also been filed against Axon, this time in New Orleans by the family of a police officer who was shot and killed after his X26P Taser (which produces the same level of charge as the X2) was allegedly ineffective against a suspect.

A fine line

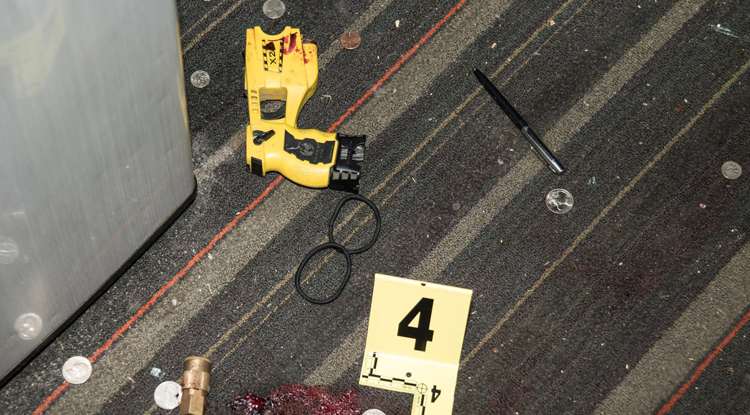

For a Taser to be effective an officer needs equal elements of skill and luck. First, an officer must hit the target. Tasers simultaneously shoot two barbed darts attached to thin, electrified wires. Both darts have to hit the target to deliver the electricity – if either one misses, no circuit is created and no electricity flows. Each dart must strike within one inch or so of the skin – or better yet, penetrate it – to create a complete electrical circuit. If someone is wearing a heavy coat or loose clothing, the electricity may not arc into the body enough to lock up muscles. There is also a chance that a person convulsing under the Taser’s power will manage to remove one of the darts – or break the wires that lead back to the Taser, ending the flow of electricity.

Where the darts strike is also important. They must be at least 1ft apart when they hit someone for the electricity to flow through enough muscle to reliably incapacitate the person.

Tasers are typically designed to work best at a specific range from the target. If officers are too far away, they are likely to miss. But if officers are too close, the Taser is less likely to halt someone because the darts will invariably not be far enough apart to lock up the muscles.

Axon’s own training materials state that using the X2 from zero to 7ft distance can result in greater accuracy, but less effectiveness. It advises officers firing at such close range to “split the belt line”, meaning land one dart above the waist and one below the waist.

The X2 manual notes that “if the probes impact in an area where there is very little muscle mass (eg, the side of the rib cage), the effectiveness can be significantly diminished”.

Over 25 years, Axon has changed its recommended spread between darts. Initially, it said the darts needed to hit only 4in apart to incapacitate someone. It later asserted that the darts needed to be 9in to 12in apart. And it now recommends at least a 12in spread between darts for electricity to flow through enough muscle to reliably bring someone down.

Axon’s earlier models were designed to work best at longer range. Most of its models, dating to 1994, had darts spread apart in a way that made them reliably effective at 7ft or more.

When the Taser X2 was released in 2011, it narrowed the angle at which the darts spread. That meant officers had to be even farther away – at least 9ft – for the X2 to be effective.

Our view is that it is better that officers have Taser as a tactical option than not.

However, none of those distances reflected the reality on the street, where violent encounters in which officers reach for their Taser are often much closer. Studies from police departments in New York and Fort Worth, Texas, found that about 75 per cent of Taser discharges take place within 7ft of a suspect. The data suggests that virtually all Tasers currently in circulation are typically not used at the ranges where they are most effective.

The X2 manual notes: “Probe spreads of less than 4in/10cm (including drive-stun) may result in little or no incapacitation effect.”

In October 2018, Axon released its first new Taser in five years, claiming it would be the most effective ever. Mr Smith promised the new Taser 7 would be “stronger, faster and smarter than any that has come before it”, although it is not yet available in the UK.

A number of modifications were introduced to address problems experienced with earlier models – including better darts and improved laser sights.

The electrical output of the Taser 7 is identical to that of the X2 – still half that of the X26. However, it focuses its energy in shorter, more concentrated and frequent bursts. Axon claims delivering electricity in that condensed manner will make the device more effective. While the power output of the X26 can vary depending on where the probes land, the X2 and Taser 7 deliver a more consistent charge regardless of the strike zone.

Axon says it is constantly improving its weapons based on feedback from officers: “The Taser 7 is the result of Axon’s commitment to develop new, innovative products and improve its existing products. Some of those developments sought to address common reasons why a [Taser] may not cause [muscle incapacitation].”

It added: “Tasers are the most studied less lethal tool on an officer’s belt. These studies, along with nearly four million field deployments over 25 years, establish they are the most safe and effective less-lethal use of force tool available to law enforcement.”

Ché Donald, national vice-chair of the Police Federation of England and Wales, said: “As with all pieces of equipment there is unlikely to ever be a 100 per cent success rate. For a variety of reasons it is not always possible for the barbs to attach in the ideal position, and I know the developers of Taser are continually working to develop and refine their equipment to increase its reliability, such as the release of the new Taser 7.

“Taser is a vital piece of protective equipment and the Federation continues to campaign for all officers who want to carry it, and who pass the assessment criteria, to be able to. The Federation pushed hard for the roll-out of X2 to replace its predecessor – the X26 – because the newer model allows officers the option of a second shot if the first has not disabled the subject.

“Our view is that it is better that officers have Taser as a tactical option than not. And we know in more than 80 per cent of occasions it de-escalates situations without the need to fire, making it extremely effective.”